The chancellor was always going to target property in the Budget, but the reality wasn’t nearly as bad as feared. Two relatively modest raids on prime property values and landlords’ incomes may not massively distort the market, but the market is nevertheless on an intriguing trajectory as we head into 2026.

The first raid came in the form of an annual “mansion tax”, to be levied on homes valued at over £2mn as of April 2026, will take effect from April 2028. The tax, which the government hopes will raise £400mn annually from 2028-29, will be a surcharge to council tax across four price bands. An additional annual charge of £2,500 for homes worth between £2mn and £2.5mn will rise to £7,500 for homes valued at over £5mn. These will increase annually in line with inflation.

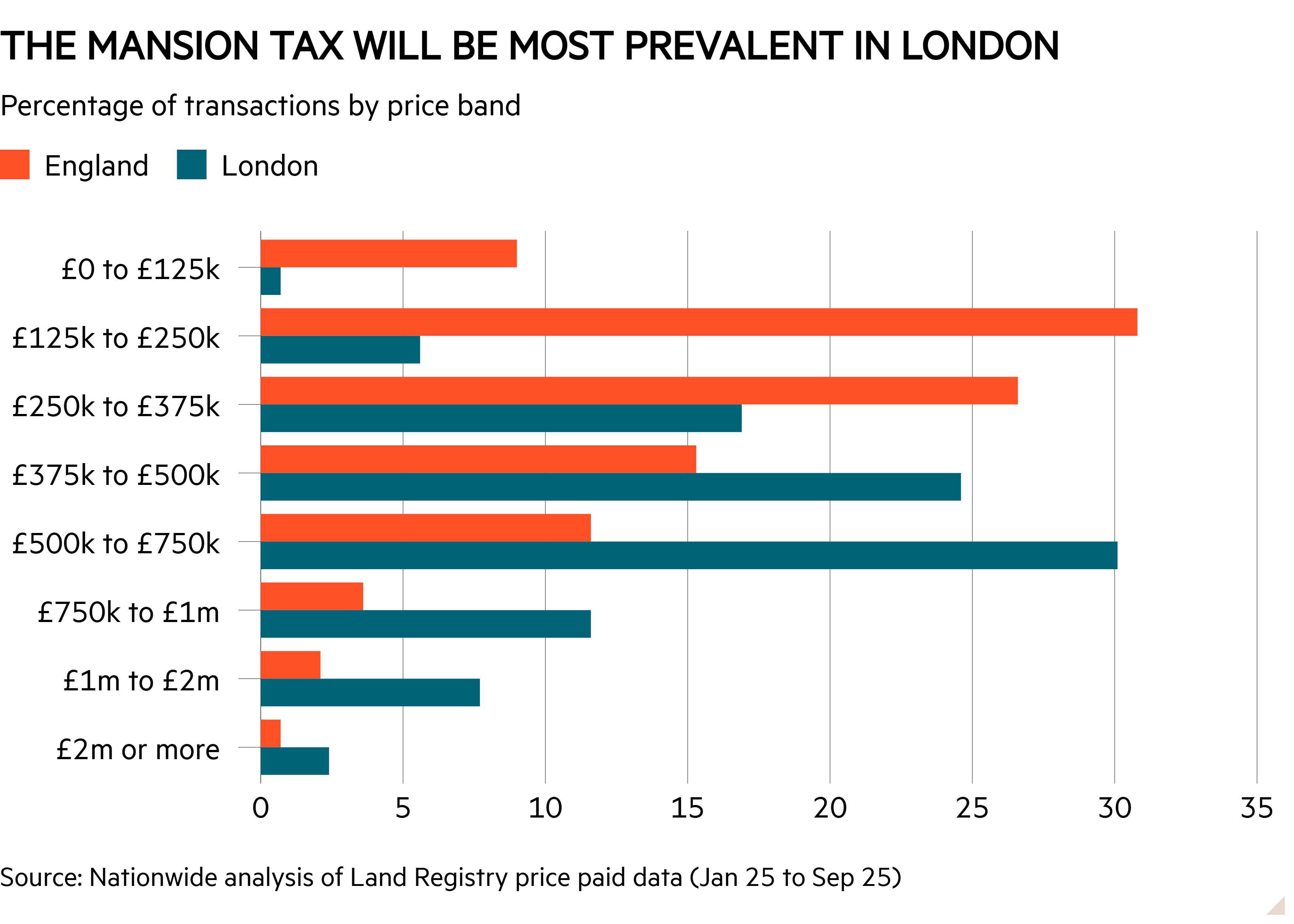

Less than 1 per cent of properties will be caught by the charge, estimates Nationwide, with the majority of these unsurprisingly in London and the south east.

The announcement is likely to have prompted a sigh of relief among many homeowners and should be viewed as “the least worst outcome”, according to Lucian Cook, head of residential research at Savills, a property firm.

Several more fearsome proposals had been trialled in the build-up to the Budget, including more punitive versions of the mansion tax and the removal of capital gains tax relief on high-value primary residences.

This uncertainty had caused “complete and utter paralysis” in the super prime end of the market, according to Alex Christian, joint head of Savills’ private office, which caters to ultra-high-net-worth buyers.

A modest flurry of activity may ensue, as previously uncertain homeowners now look to transact. “We have seen people come to market. It has brought buyers out of the woodwork,” says Cook.

“There’s definitely new activity that we would not expect for this time of the year,” notes Claire Reynolds, head of UK residential sales at Strutt & Parker, an estate agency that focuses on the premium end of the market.

There is also scope for a small recovery in prime property values. “It depends on how much of the [pre-Budget] uncertainty was priced in,” notes Cook. “If buyers and sellers had overcompensated [with valuation adjustments], there’s the prospect of a bounce in values.”

In the medium term, few expect the new tax to deeply distort the market, including at the top end. “It is a relatively small amount for people who own homes of that value,” says Reynolds.

“It hasn’t been mentioned to me once,” observes Christian of the tax.

As for the main market, “the changes to property taxes . . . are unlikely to have a significant impact,” says Robert Gardiner, chief economist at Nationwide.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Second-order effects

There is still a risk of price bunching, however, as buyers and sellers price transactions at just below the thresholds. Not only will this reduce revenues from the mansion tax itself, but also those from other property taxes, such as capital gains tax and stamp duty. The Office for Budget Responsibility, a government spending watchdog, estimates that this will reduce revenues by £0.1bn next year, and £0.2bn from 2028-29 onwards.

As for other effects, valuing prime property is complex: fewer transactions inhibit price discovery, bespoke features are more common, and buyers and sellers are both likely to be more discerning.

This leaves “the prospect of appeal quite high”, says Cook, especially either side of the “quite tight” £2mn-£2.5mn lowest band. The government will doubtless hope that the surcharge isn’t sufficiently large to prompt legal action.

An already stretched Valuations Office may find itself hard pressed to value the hundreds of thousands of potentially eligible properties before the mansion tax takes effect in 2028, with or without disputes.

The government will also conduct consultations on reliefs and exemptions during this period, including for those deemed too ‘cash-poor’ to pay the surcharge. These are often long-term owners of London properties whose values have rapidly appreciated.

This all begs the question of whether an additional £400mn of annual revenue is worth the additional administrative burden.

A greater surprise than the mansion tax was the government’s 2 percentage point increase in income tax on property income, effective from April 2027. The basic, higher and additional rate will increase to 22 per cent, 42 per cent and 47 per cent, respectively.

This will come as yet another blow to landlords. The recently passed Renters’ Rights Act could make it harder for them to pass on the increase to their tenants, seeing as tenants can now contest rent rises in front of a tribunal if they feel those increases exceed the market rates.

“This will act as another push factor for small landlords,” says Cook. More housing stock could come on to the market as a result. Landlords with larger portfolios should be better placed to cope.

All about affordability in 2026

Looking ahead to 2026, affordability issues will continue to plague the housing market. UK house prices are about six times the average salary, rising to nine times in the capital, according to Nationwide. There was nothing in the Budget to support first-time buyers, which leaves aspiring homeowners hoping that lower mortgage rates will come to their aid.

The market is pricing in three further 0.25 per cent rate cuts through to the end of 2026, taking the Bank of England’s base rate to 3.25 per cent. But the 3.6 per cent five-year swap rate, which lenders use to price mortgages, is already pricing in much of this reduction.

Prices are already competitive, leaving little scope for mortgage prices to fall. “Mortgage rates will probably sit pretty close to where they are now,” says Andrew Goodwin, chief UK economist at Oxford Economics, a consultancy.

This means little chance of mortgage rates falling below their current prohibitive levels of around 4 per cent.

Indeed, given current fierce competition, “banks are more likely to try to restore margins than lower them”, adds Goodwin.

Higher mortgage rates discourage mortgage holders on lower rates from refinancing, whether to upsize, downsize, or move with a new job. This brings inefficiency to the housing market.

They also price prospective first-time buyers out of the market. First-time buyers are currently spending a prohibitive 21 per cent of their gross income on mortgage payments, housing analyst Neal Hudson wrote in the Financial Times. “[This is] more in line with what people pay in a housing bubble,” he said.

Continued constraints will keep demand muted, discouraging housebuilders from bringing too much new supply on to the market. This bodes ill for the government’s target to build 1.5mn new homes this parliament.

As for pricing, “supply will be quite constrained which should support price growth going forward”, says Goodwin.

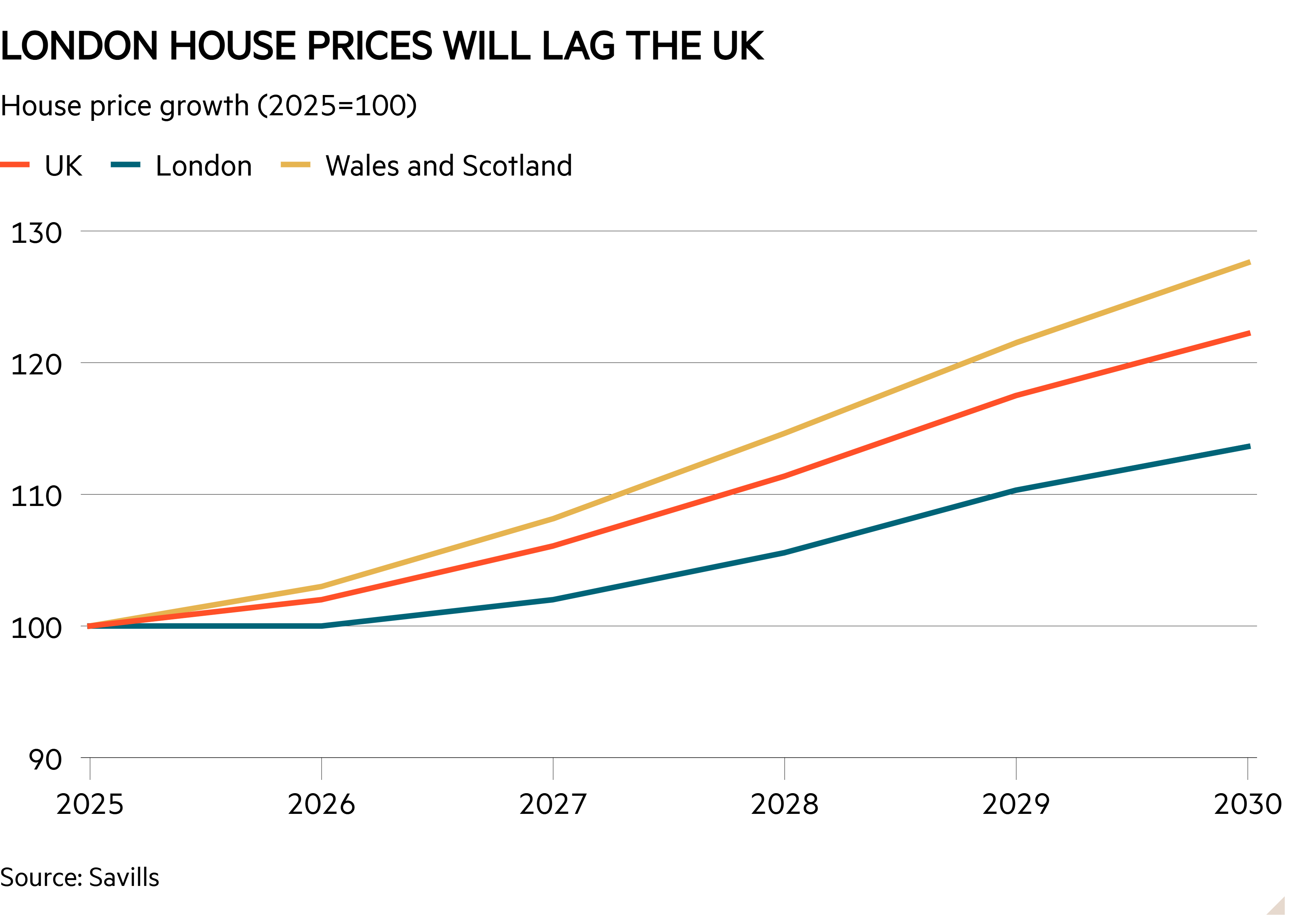

Even so, prices are unlikely to take off in 2026. Cook does not expect the Budget to materially alter Savills’ current forecasts, which are for 2.0 per cent price growth next year, broadly in line with 2025. This rises to at least 4 per cent per year through to 2030.

Regional growth rates will vary significantly. Cook expects it to be strongest in the north, Wales and Scotland, but weaker in the south, with no growth forecast at all for the capital.

“London will underperform the rest of the UK,” says Cook. “You still have significant deposit barriers for first-time buyers, you still have greater affordability pressures, and you still have tenants committing a greater proportion of their income to rent.” The outlook is discouraging.