They’re pitched as a green energy miracle – but for homeowners, giant solar farms may spell financial gloom.

A sweeping new study from Virginia Tech has revealed that homes located within three miles of a utility-scale solar facility lose around 5 percent of their value shortly after installation, according to Cardinal News.

But while suburban homeowners take the hit, farmers and landowners are cashing in.

The same study found that agricultural and vacant land within two miles of a solar plant saw prices soar by nearly 19 percent – as developers scramble to lease land for future expansion.

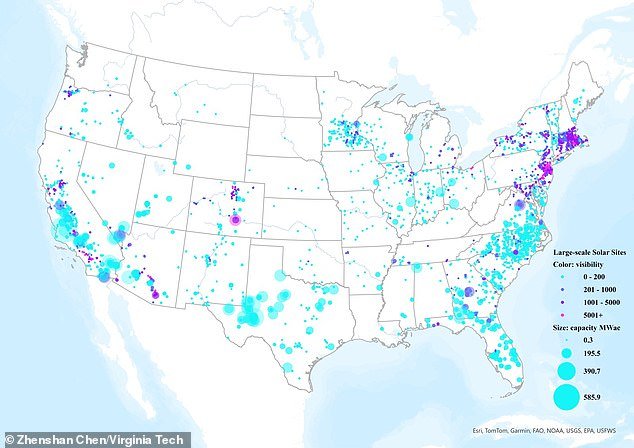

Researchers analyzed 8.8 million real estate deals near 3,699 industrial-scale solar facilities across the United States.

These aren’t rooftop panels – they’re sprawling fields of ground-mounted panels stretching across hundreds of acres.

The Virginia Tech-led team built a detailed model to determine the impact of proximity, visibility and terrain – even factoring in elevation to see whether solar sites were visible from nearby homes.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t the view that affected home values. Whether or not residents could see the solar farm, the price dip remained roughly the same.

A map of the large-scale solar capture sites the team looked at and their level of visibility from nearby properties

Members of the team involved in the study are pictured from left: Chenyang (Nate) Hu, Darrell Bosch, Zhenshan Chen, and Xi He visit a large solar farm in southeastern Virginia

A view of Hope Farm Solar from Derby Lane in Cranston, Rhode Island. Homes close to solar plants can lose up to 5 percent of their value

And the hit didn’t last forever. Prices typically rebounded within 10 years – but the short-term impact could be devastating for those trying to sell soon after construction.

Meanwhile, homes sitting on larger lots – more than five acres – were largely immune to the drop.

Experts believe the agricultural value surge is due to land near existing solar sites being seen as prime real estate for expansion.

Developers prefer building next to existing infrastructure, making adjacent farmland highly attractive.

But the study authors warned this may drive up rents for tenant farmers, even as landowners reap the benefits.

The findings come as Virginia ramps up its solar footprint following a 2020 law mandating Dominion Energy and Appalachian Power go carbon-free by 2045 and 2050, respectively.

And while the research covers the entire country, the battle over where to build solar farms is raging fiercest in rural Virginia – where locals are torn between environmental goals and personal financial loss.

The researchers stopped short of drawing sweeping conclusions, noting that the results vary by region and circumstance. Still, the data points to a clear trend: solar farms do impact nearby property values.

The new study comes from Virginia Tech. Pictured above Richmond – the capital of Virginia

Solar farm, Simi Valley, California, USA, aerial view. The researchers stopped short of drawing sweeping conclusions, noting that the results vary by region and circumstance. Still, the data points to a clear trend: solar farms do impact nearby property values

The 13-megawatt Fort Lupton Solar Farm in Colorado generates electricity for United Power, a rural electric cooperative.

The study was led by Zhenshan Chen, an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics at Virginia Tech, along with lead author Chenyang (Nate) Hu, who recently earned his Ph.D.

The team also included faculty members Wei Zhang, Xi He, Darrell Bosch, and Pengfei Liu of the University of Rhode Island.

The full research was published in June in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Chen urged policymakers to get ahead of the issue and consider steering future development toward brownfields – previously developed, abandoned industrial land – instead of prime farmland.

But building solar farms on brownfields comes at a price. While the EPA offers financial help for cleanup, many sites are still too expensive for developers to touch.

The Virginia Tech findings echo a growing – and conflicting – body of research on the solar-real estate question.

A Loyola University study last year found that homes near solar plants in the Midwest actually saw a bump in value – between 0.5 and 2 percent.

But a 2023 analysis by Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and the University of Connecticut found that homes in six states lost 1.5 percent of their value when located near large solar sites.

Aigen CEO Kenny Lee (L) and CTO of Aigen Richard Wurden (R) inspect a solar-powered autonomous AI robot at Bowles Farm in Los Banos, California

The study was led by Zhenshan Chen, an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics at Virginia Tech (pictured)

Meanwhile, a separate March study from Virginia Commonwealth University found that more than 30,000 acres of land in the state are now occupied by utility-scale solar projects.

And cropland has taken the brunt of it.

While cropland makes up just 5 percent of Virginia’s total land, it accounts for 28 percent of land used for solar – sparking fears that farmers could be squeezed out as demand rises.

Forests, by comparison, have been affected more proportionally – around 50 percent of solar sites were built on land that was previously wooded, mirroring Virginia’s broader forest coverage.

As the solar boom continues across America, the message is clear: these projects might help fight climate change – but they’re reshaping the housing market in their shadow.