The British obsession with home ownership is widely considered to be as much of a national characteristic as German industriousness or the Italian devotion to espresso. But if it is an obsession, is it becoming increasingly unhealthy? Unable to consummate their desire to buy, many are not so much in love with property as desperately stalking it. The gap is ever widening between those who already own homes or can call on the bank of mum and dad to help them get one, and those for whom ownership seems forever out of reach. At the same time, renting has become even less attractive, with rents having risen 21 per cent over the past three years and insecure, short-term tenancies.

All the major political parties went into the past election promising more homebuilding and support for those trying to get on the housing ladder. The most recent government spending review also promised £39bn to fund a new 10-year Affordable Homes Programme and £16bn to create a new National Housing Bank. But what if this does not so much curb the obsession as feed the addiction? Would we not be better to question the imperative to own and take renting seriously as a valid, grown-up option?

There is also a growing consensus that tenants’ interests need to be addressed, with the private rental sector in particular in need of an overhaul. Although the Conservatives didn’t get their renters reform bill through parliament before the 2024 election, their manifesto included a promise to pass it. Labour picked up the baton and presented its renters’ rights bill last September. The bill has passed its third reading in the Commons and this week the report stage-landed in the House of Lords; it is expected to come into effect in early autumn.

The renters’ rights bill intends to increase tenant security by making it harder for landlords to up rents or evict merely for their own convenience. It will also ban discrimination against prospective tenants on benefits, introduce safeguards on the condition of properties, and even make it easier for renters to bring their pets.

But Nathan Emerson, chief executive of the letting agents’ body Propertymark, claims that “88 per cent of landlords have no confidence in the current private rental sector due primarily to the bill, and more than a third plan to leave the sector altogether this year”.

Although supportive of improvements in tenants’ rights, Liam Bailey, head of research at real estate consultancy Knight Frank, warns “there are consequences of loading costs on to landlords: reduced supply [of property to rent] in the market, and a rise in rent over time”.

However, the campaigning housing NGO Shelter described the bill as a “once-in-a-generation opportunity to overhaul the private renting sector”. Could it also be the cue for an epochal shift in attitudes to ownership?

It is perhaps not surprising that home ownership in the UK is so prized, since for centuries it brought with it not just status, but concrete rights. Until the early 19th century, voting for county and borough representatives was restricted to men of property, usually above a minimum value, and only some tenants. The Great Reform Act of 1832 extended the electorate in England and Wales, but property ownership remained the most common form of eligibility to vote. Similar legislation was passed for Scotland and Ireland. The Representation of the People Act of 1867 and its Scottish and Irish counterparts reduced the value of property owned as a requirement for voting but was similarly limited in effect. It wasn’t until the Representation of the People Act of 1918 that the franchise was extended to all men, and some women.

It may be that in our collective memory home ownership is still associated with a broader social status. But that does not mean Brits are especially likely to be homeowners by international standards. The proportion who own their own home peaked at around seven in 10 at the start of the millennium and has settled at around 65 per cent. This is lower than Norway, Portugal, Spain and Italy, where upwards of 70 per cent of people live in their own homes. In the global chart, the UK sits below the EU and Canada, and above the US, Australia, France and Sweden.

Even this level of home ownership is an historical anomaly. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports that in 1918, 77 per cent of households were rented, almost all privately. By 1961, the biggest change in tenure patterns was that by then a quarter were socially renting compared to 34 per cent renting privately; homeowners were still in a minority. It was not until 1971 that Britain had as many homeowners as renters; in 1981, 58 per cent of households were owner occupied.

The Thatcher boom of the 1980s is usually thought to have supercharged the property market, a key driver being the right for council tenants to buy their homes at a discount on market prices of at least 33 per cent. The right to buy “definitely boosted owner occupation, and more importantly, it changed who was a homeowner, which was probably the most radical aspect of the Thatcher period”, says Rory Coulter, associate professor in geography at University College London. However, the policy didn’t change the rate of increase in ownership very much, which remained quite steady until its near 70 per cent peak at the turn of the millennium.

What did increase significantly were house prices. This was fuelled at least as much by the deregulation of mortgage finance as it was by the council house sell-off, says Coulter. “There’s one school of thought which says that much of the house price boom has been caused by demand, which has been pushed up by access to credit.”

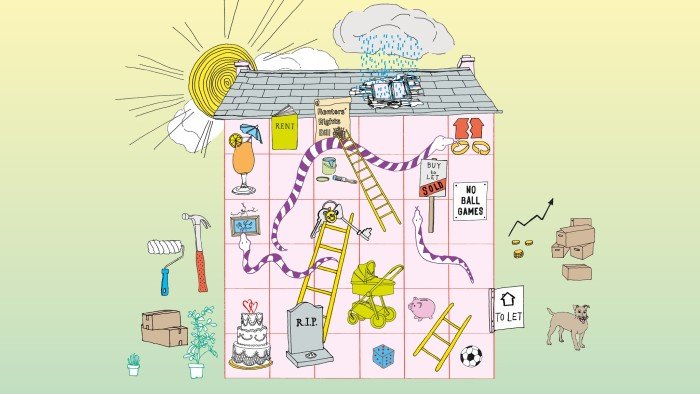

But perhaps the most important impact of the 1980s was on attitudes. Take the phrases “property ladder” and “housing ladder”. We talk of these as though they were a permanent and natural feature of modern life. But as Google’s Ngram viewer shows, the terms were uncommon until the 1970s and only shot up in usage at the turn of the millennium, peaking in 2008. The idea that everyone needs to climb the property ladder, with all the anxieties that come with it, is far newer than we tend to assume. Even in the early days of the Thatcher plan for a “property-owning democracy”, more people wanted to own a home but most had not yet bought into the idea that doing so would be the start of a series of trade-ups.

The “property ladder” came to the fore in an unusual period when interest rates, transaction costs and taxes were all low, lending was easy and prices kept going up, says Bailey. “Your cost of moving didn’t seem to matter because if you held a property for two or three years you were always up on the trade.” He believes that with stamp duty now much higher and prices flatter, “the idea of a ladder where you move slowly up property sizes doesn’t work. So people will stay put for longer and they’ll extend and enhance their current property to try and make it work for them.”

The other big legacy of the era is the emphasis on property as an investment. “Bricks and mortar” have long been considered a safe place to put your money, but the notion that it would help it to grow is much more recent. UK house prices increased very gradually until the 1970s and only started to shoot up ridiculously in the mid-1980s. That heyday didn’t last long: in real terms, house prices are now still lower than at their 2007 peak.

Changes in the housing market over the decades have not just affected owners. The nature of renting has been evolving for more than 100 years. For the majority of the past century, most renting was from private landlords. Social renting grew from nothing at the start of the 20th century to a peak of 31 per cent in 1981. It has been declining ever since to around 16 per cent today. At the same time, private renting was in long decline, squeezed between the rise of ownership and social renting. Since 2008, however, private renting has been the only form of tenure that has seen underlying growth.

The social housing stock has been in decline, from around 5.5mn dwellings in 1980 to just over 4.5mn in 2024. The reduction has been due to a combination of the right to buy and the demolition of old homes without new homes replacing them. Shelter reports that just 150,000 social homes were built in the 2010s compared with 1.24mn in the 1960s. More social rent homes were built in 1969 than in the past 13 years combined. The most recent government figures show that there are 1.33mn households on local authority social housing waiting lists, a number that has been steadily increasing from 1.2mn in 2017.

At the same time, in the private sector, tenants are vulnerable to the whims of landlords. Section 21 no-fault eviction notices allow landlords to ask tenants to move out at two months’ notice, without the tenant having done anything wrong. They are due to be abolished by the renters’ reform bill, a move Coulter says is “long overdue”.

The long historical view of British housing combined with a level-headed assessment of the current state of play suggests that any obsession with ownership we might have is not deeply rooted in the national psyche but has been nurtured by decades of policy that have incentivised buying over renting.

“It’s quite rational to want to become a homeowner in this country,” argues Coulter. “There are supportive policy measures which make home ownership attractive, like: you don’t pay capital gains tax on the sale of your primary residence. Home ownership has been quite attractive in terms of house price inflation and has helped to generate wealth for people that own their home. But also, what’s the alternative?”

Just as policy has made owning more attractive, it has made renting less so. Short-term tenancies introduced as the default renting contract in 1988 suited what was then the “traditional private renter”, as Coulter calls them — “a student, someone who’d recently arrived in the country, a young professional in a new city as they started a new job. But now low-income families and single parents are living in a tenure that is unstable by design.”

As behavioural economists have argued, if our choice environment changes, so do our preferences.

This, not culture, perhaps explains why renting is more popular in Germany than in Britain and most other European countries. Tenants in Germany have far greater security of tenure, which means that while Brits reside on average only two and half years in a rented home, Germans stay put for 11. Rent controls also mean that Germans pay a substantially lower proportion of their income on rent than the British. Significantly, German renters have more political voice. The German national tenants’ association, Deutscher Mieterbund (DMB), represents around 3mn tenants. There is no such body in terms of scale or reach in the UK.

The renters’ rights bill would seem an attempt to move private renting more in the direction of Germany. Social renting, however, is still seen as very much the poor relation; reports over recent years have found a large proportion of social housing tenants experiencing stigma because of where they live. Austria shows this is not inevitable. It has a long history of desirable social housing that makes up nearly a quarter of the country’s housing stock, and attracts both middle and low-income households. A report by the Austrian Institute of Economic Research also suggests that increased social housing provision drives down rents in the private sector.

There is little doubt that Britain needs a better mix of housing provision, including higher-quality, more secure rental options. One increasing route is the rise of build-to-rent developments by large companies. “Lots of the towers you see in London are being built by companies that will own and rent that block,” says Bailey. “From a government perspective, it ticks the box of a professional landlord who’s got skin in the game for the long term. They want to create an attractive environment for tenants so they’ll be fully occupied and they’ll be able to raise rents over time.”

If renting is to cease to be seen as a consolation prize for those who can’t afford to buy, changes in regulation and policy will have to bring about a change in attitude. Around the world, whatever the levels of property ownership, home matters to people. What makes somewhere your home is not necessarily whether you own it but whether it is yours to live in, for as long as you want. Consider the Maori, for example, who used ideas of usage rights rather than ownership to determine who could work or live on a piece of land. There was no need to think of owning a home in order to feel it was yours to live in.

Many council house tenants often used to feel the same. I remember many in the 1980s who had no interest in taking up the option to buy their homes. They knew they had a home for life and the council would take care of repairs. Why would they take on the responsibilities of mortgage, maintenance and insurance? They would not get a better home as a result.

Nor would they have become owners overnight anyway. Forty-three per cent of UK homeowners have a mortgage and until it is paid off, the lender holds the deeds. If we were to insist that a person does not truly own their property until all loans secured on it are paid off, only 37 per cent of the population would count as homeowners.

House & Home unlocked

Don’t miss our weekly newsletter, an inspiring, informative edit of the news and trends in global property, interiors, architecture and gardens. Sign up here.

And bricks and mortar can drain funds. Owning in retirement sounds reassuring, but without a large pension, what happens when a £10,000 bill to fix the roof comes in? This has to be a worry for many when the median retired household income is around £30,000 per year. The knowledge that someone else will sort out any maintenance issues gives more reassurance than a title deed.

The rented roof can feel as much like home as one that is bought. And if renting were made more attractive, more would likely choose it. That doesn’t necessarily mean home ownership would lose its aspirational appeal. But as Coulter says, “Actually getting to the point of doing something about it is the hard bit.”

Julian Baggini is an author and philosopher

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ft_houseandhome on Instagram