The UK is one of several countries to score a perfect ten for its policy and technology environment for conventional pumped hydro storage (PHS) in a report published by Energy Systems Catapult.

The report, Mission Innovation – Long Duration Energy Storage, breaks down the viability of deploying long-duration energy storage (LDES) systems in a number of countries, and across a number of technologies, awarding countries scores out of ten to rank the supportiveness of the current political and economic environment for new LDES deployments.

In general terms, the report finds that countries with a number of LDES deployments are more attractive destinations, as these older projects demonstrate the business case for new deployment in the country, and that countries with supportive policy frameworks for LDES are among the most attractive.

The UK scores well in both metrics, with the report referencing the Net Zero Innovation Portfolio, a source of funding for low carbon technologies and systems, as a particularly supportive programme. The initiative is a £1 billion investment that has already supported investments in AI in the renewables sector and space-based solar power, and in 2023 granted £30 million for LDES projects in particular.

Supportive policies driving LDES deployment

Several other countries received full marks for their policy support for PHS, including Australia, Germany and the US. The German policy landscape is very similar to that of the UK, with both countries offering grid fee exemptions, carbon pricing schemes and revenue stacking opportunities for LDES projects, incentivising new investments into the sector.

However, the Australian market is more varied, with a number of financially supportive mechanisms for new storage projects. These include seed funding for large-scale storage projects delivered through the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA), and loans available for the installation of residential solar PV and energy storage systems, which is less relevant for PHS in particular, but demonstrates the widespread government support for energy storage across the Australian energy sectors.

The report also notes that the Australian National Electricity Market, which operates in the east and south-east of the country, has set a “resource adequacy target”, to maintain a reliable supply of electricity from clean energy sources. While the UK’s National Energy System Operator (NESO) has published “a few resource adequacy studies” according to the report, these are less legally binding, and thus influential, than a legal target.

Further investments in supportive policies, particularly from the financial side, could help bolster the UK’s $69 million investment already made into its Longer Duration Energy Storage Demonstration (LODES) programme, which was named as a supportive policy in particular by the Energy Systems Catapult report. The government has set a target of 20GW of LDES deployments, which would be a significant increase from the 2.8GW of capacity currently in operation, all of which is in the PHS sector.

Strengths and opportunities for other technologies

In addition to its work in the PHS sector, the UK is also a leader in other LDES technologies, notably high-density PHS. The UK received a score of eight for its work in this regard, with no other country scoring higher, and the average among all countries profiled just five. Australia, Germany and the US, which scored equally to the UK on PHS attractiveness, scored seven, four and four, respectively, for high-density PHS.

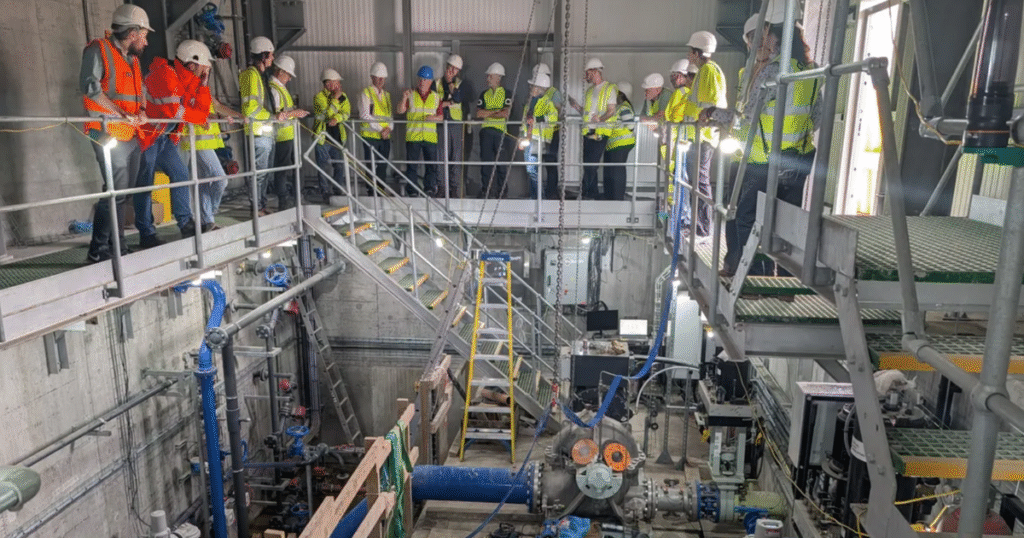

Part of this stems from the UK’s investment in the technology; last year, RheEnergise completed work at the Cornwood research and development high-density PHS in Devon, a combined research facility and demonstration plant that received over £140,000 in government funding through the LODES scheme.

While the UK’s scores were generally high across the 16 technologies profiled—receiving an average score of 6.6 across all of them—there was one notable exception, below water compressed air energy storage (CAES), for which the UK scored its lowest mark, one. The report notes that the UK’s geography is “not suitable” for the technology, so this is something of an outlier; Germany and Denmark also received a score of one for the technology.

However, there are some technologies in which the UK could improve its performance, not being hampered by geographical limitations as the country is for CAES. One example is that of Carnot batteries—power-to-heat-to-power batteries—for which the UK scored a five, with just one project in the pipeline, a demonstration project delivered through the University of Birmingham that is part of an EU €4 million investment into the technology

France, meanwhile, received the highest score for the technology—an eight—as there is already a Carnot battery demonstration plant in operation in the country.

Advancing the technological maturity of technologies such as Carnot batteries will be essential if the UK is to build a more attractive investment landscape for LDES technologies that are presently thought of as early-stage in the UK. Fortunately, the growth of LDES technologies around the world could help break down some of these barriers to more widespread implementation.

“LDES technologies are gaining traction globally, with some countries already implementing targeted market mechanisms and others showing strong potential for future deployment,” said Dr Rosie Madge, systems engineer at Energy Systems Catapult. “Our analysis highlights that suitable markets and supportive policy frameworks are key to unlocking opportunities for LDES.”