If there’s one thing that the Conservatives and Labour can agree on, it’s that the UK economy needs businesses to invest more.

This is hugely important for any economy because investment underpins technological progress, helping to improve a country’s productivity. But business investment in the UK economy has essentially flat-lined as a share of GDP since 2000, meaning the UK has fallen behind its global peers.

If business investment had matched the average of France, Germany and the US since the financial crisis, GDP would be nearly 4 per cent higher today, according to the Resolution Foundation.

That’s equal to a £1,250 increase in annual wages.

There’s a range of possible reasons why business investment is low, but one of the main culprits – at least in recent years – has been the complete lack of political stability.

There has been a huge amount of churn in a whole range of different departments. Looking at the business department specifically, there have been ten different ministers since 2010.

Indeed, the department itself has been revamped four times since the financial crisis, with each rebranding revealing a subtly different emphasis.

First there was the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform, which became the Department for Business Innovation & Skills during the Coalition years. Theresa May’s Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy then followed, before this was replaced by the Department for Business and Trade in 2023.

Related? Sure. The same? No.

Probably the largest shock to business was the Brexit vote in 2016 and the subsequent failure of the Conservatives to generate a consistent strategy following the decision.

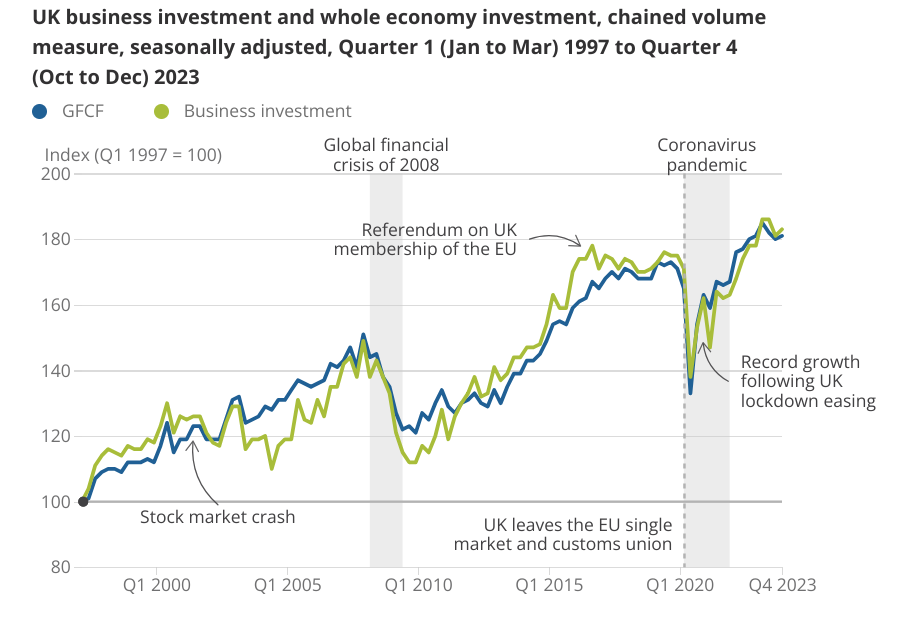

The impact is easily seen in the trend of UK economy business investment after the referendum. Having been on a steadily upward path since 2010 (although still roughly flat as a share of GDP), business investment was then stagnant from the Brexit vote until the pandemic.

It’s easy to understand why. Investment involves making a long-term judgement about the performance of an economy. It is very difficult to make a long-term judgement if there’s significant uncertainty about an economy’s main economic policy.

But then there’s the good news.

Since the pandemic, investment in the UK economy has increased in line with the G7 average and it is now above its Brexit level. In 2023, only Italy recorded a faster rate of investment growth than the UK among G7 nations.

It seems clear that both parties are committed to ensuring that this trend continues. In the Autumn Statement last year, Jeremy Hunt eschewed potentially more attention-grabbing tax cuts for the full expensing policy, which cost £10bn.

Full expensing, which Hunt described as the largest tax cut for business in modern British history, allows businesses to essentially write off the cost of investment against a range of qualifying equipment.

Hunt has also committed to expanding this programme policy further when the fiscal position allows.

Then there’s the various plans to unlock a wave of investment from City firms investing in everything from infrastructure, through Solvency II, to start-ups, through the Mansion House compact.

Rachel Reeves, the Shadow Chancellor, has committed to building on these policies, pledging a “genuine partnership” between “dynamic business and strategic government”.

In her Mais lecture, Reeves promised to publish a roadmap for business taxation, covering the entire parliament, within the first six months of entering office. She also committed to keeping corporation tax at 25 per cent, the lowest level in the G7.

This, she said, would enable businesses to “plan investment projects today, with the confidence of knowing how their returns will be taxed for the rest of this decade”.

Perhaps more important than anything Reeves can announce, there’s a sense that a new Labour government with a healthy majority could offer business stability.

As Simon French, head of research at Panmure Gordon, pointed out: “The most important aspect for success of Securonomics may be the least sophisticated thing of all: economic agents just relieved at a political reset, and that a change in administration triggers refreshed UK enthusiasm”.