Illustration: Tracy Worrall

10 min read

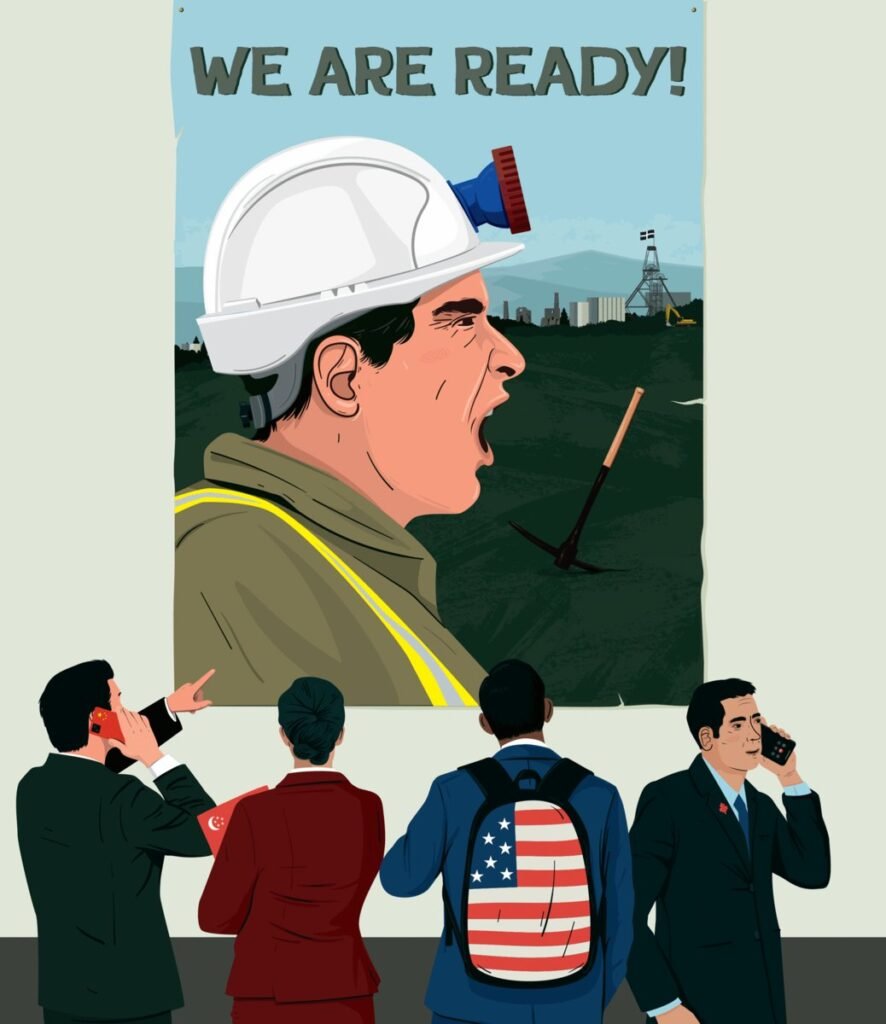

The UK has deposits of critical minerals but has stopped mining them. Sophie Church hears that, if we don’t take advantage of our assets, others are waiting. Illustrations by Tracy Worrall

Cornish lads are fishermen, and Cornish lads are miners too. But when the fish and tin are gone what are the Cornish boys to do?

In 1994, Cornish shanty singer Roger Bryant wrote Cornish Boys, an ode to Cornwall’s dying mining industry. The price of tin was falling, and the mines that had supported Cornish communities for hundreds of years could not afford to stay open. Four years after Bryant wrote his shanty, the UK’s last remaining tin mine, South Crofty, closed.

Yet pockets of critical minerals remain nestled across our Isles, from County Tyrone to the Highlands and down to Cornwall. The UK has some of the largest reserves of lithium in Europe, while Hemerdon Mine in Devon boasts the second-largest deposit of tungsten in the world.

Used in many of the technologies we see today, from solar panels to mobile phones to jet engines, China has invested heavily in critical minerals and held prices low. China now produces more than 50 per cent of 17 of the top 27 critical mineral groups, and refines 90 per cent of the world’s rare earths. Xi Jinping’s ‘Belt and Road’ initiative has seen China control critical mineral extraction on five different continents.

South Crofty and other critical minerals mines around the world have been unable to compete.

But as the world wakes up to its over-reliance on China for critical minerals, the UK is finally recognising its own value. In July, Rachel Reeves visited South Crofty, which has now reopened thanks to government funding. After speaking a few words in Cornish, in her hard hat and high-vis, the Chancellor went on to say that the £28.6m grant from the National Wealth Fund (NWF) could lead to the creation of 1,300 jobs. The team at South Crofty now hope to start commercial extraction of tin by mid-2028.

Chris understands the opportunity, but he also understands the requirement for investment in processing

In September, the NWF invested another £31m into Cornish Lithium alongside increased funding from Techmet, a critical minerals investor. Then-communities secretary Angela Rayner designated Cornish Lithium’s Trelavour Hard Rock plant a ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project’.

“It’s really hard to articulate this groundswell of hope that is coming back to communities that for decades have been deprived,” says Perran Moon, Labour’s MP for Camborne and Redruth.

“We’re seeing record numbers of apprenticeships in some of our businesses. We’re seeing young people really engaging with geology. And we’re seeing our further education college maxed out in its number of construction workers and engineers.”

The UK’s mining industry is also revelling in the government’s support.

“What projects internationally are competing for is capital, and that’s where, for instance, the NWF investment in Cornish Lithium – which was instrumental in attracting other funding from the private sector into the project – was so important,” says Mike King, business development and government relations vice president of Cornish Lithium.

Being made a ‘Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project’ helped “tremendously” in giving certainty to investors, King adds.

Strategic Minerals, which is exploring the Redmoor Tungsten-Tin-Copper project in Cornwall, has now unlocked over £750,000 in grant funding. The company matched this via its parent company to access a further £1.5m.

“We’ve significantly increased our market cap through that positive news flow and showing how good a project we have here,” says Dennis Rowland, managing director at Cornwall Resources Limited, which is working on the project.

But financial support and photo opps for the Chancellor may be the simpler of government’s tasks. Now, all eyes are on its Critical Minerals Strategy (CMS), which, delayed since the spring, is expected to be published this month.

Chris McDonald, industry minister in the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (Desnz) and the Department for Business and Trade (DBT), is driving the strategy. Previously the chief executive officer of the Materials Processing Institute, McDonald is a welcoming face to those supporting UK critical minerals.

“Chris has got a lot of experience in this sector,” says Moon. “That really helps because he understands the opportunity, but he also understands the requirement for investment in processing. He’s in Stockton North; he understands the importance of the community side, of making sure there’s the right housing and social care.”

“We need the government to be ambitious and forward looking, and back the Cornish-Celtic Tiger – because we will roar if we’re given a chance,” he adds.

McDonald recently attended an event in No 11 hosted by Reeves, to which SMEs from the South West and North East were invited. Nick Pople, the managing director of Northern Lithium, who was also there, said McDonald showed he understands the UK must move at pace to secure its supply chain.

“He agrees that we need – and I would hope that the government and Rachel would agree – to be producing as much lithium as we can domestically in the UK as quickly as we can,” Pople says, “to ensure that we’ve got security of supply within the UK for the UK industry.”

Working together, Northern Lithium and Cornish Lithium could produce 50 per cent of the UK’s demand for lithium – essential for electric vehicle batteries – by 2035, he adds.

The previous Conservative government published a critical minerals strategy in 2022, which was updated in 2023. But King says the Labour government – and Moon’s dogged Cornish MP colleagues, working from their shared Westminster office – have been more “politically active” in raising awareness of critical minerals.

However, Labour has prevaricated over the CMS – drafting the document, then drafting again – leaving a strategic vacuum for the sector.

“The critical mineral strategy suffers and benefits from a lot of the same things that have been there with other strategies with this government,” says Dan Marks, research fellow for energy security at think tank Rusi.

“They are thinking about it quite carefully, and have been moving in the right direction, making some sensible changes and putting some money behind it, but moving incredibly slowly and lacking the more radical changes or strategic thinking that would really move the dial.”

Whitehall’s sluggishness is proving harmful. In October, UK-based mining company Pensana scrapped its £250m critical minerals processing plant beside the Humber – a project that promised to create 126 jobs – to move its refining operations to the US.

Either UK PLC takes advantage of the Cornish opportunity, or international investors will

“Europe and the UK have been talking about critical minerals for ages,” Pensana’s chairman, Paul Atherley said. “But when the Americans do it, they go big and hard, and make it happen. We don’t; we mostly just talk about it.”

For European countries firing up their defence industries, accessing secure sources of critical minerals has become vital. In July, the European Commission’s first ever stockpiling strategy concerned plans for food reserves and medical equipment – but also critical minerals.

Yet the UK defence industry has been left rudderless while it waits for the CMS. Last week, The i reported that the UK risks falling behind in the race to access critical minerals used in F-35 fighter jets.

Marks thinks there has been a “massive oversight” in Keir Starmer’s government to incentivise the UK defence industry to secure its own critical minerals supply chains. “I don’t get the sense that defence industries are expecting to have to do anything about this any time soon,” he says. “If they’re not, then that’s a massive vulnerability.”

Of the drones currently being made in the UK, for instance, around 90 per cent of their flight controllers – the core electronic boards managing flight stability, sensors, and controls – are made in China, The House has found.

As the UK slowly wakes up to the potential of mining its own underground stores of lithium, tin and copper, so too has China.

While official Chinese delegations have previously visited the UK to learn about our critical minerals sector, China is now sending a delegation from its Sichuan Provincial Natural Resources Investment Group (SPNRIG) – a capital investment company focusing on the energy industry – to the UK, The House has learned.

The delegation comprises 11 senior representatives primarily responsible for investment and strategic development at the company.

Bonjoe Education, a London-based company that specialises in such exchanges between the UK and China, will be hosting the group. Bonjoe Education’s programmes have fostered an “understanding of different cultures” and have had “great influence” on communities at home and abroad, its website reads. Bonjoe Education declined to comment.

SPNRIG has also been reaching out to specialist critical mineral organisations in the UK, The House understands.

While the aims of the visit remain unclear, industry figures have reason to fear. Earlier this year, British-based Anglo American sold its Brazilian ferronickel operations in Brazil to MMG Singapore, whose largest shareholder is China Minmetals, a Chinese state-controlled company. Critics warned this would leave Beijing with greater control over critical minerals vital to the UK’s defence, clean energy and industrial sectors.

“Ultimately, either UK PLC takes advantage of the Cornish opportunity, or international investors will,” says Moon.

“We have international visitors who come and look and talk to our businesses all the time. I’m very, very hopeful that the government is not going to take their eye onto other things and allow those international investors to dominate the Cornish critical minerals opportunity.”

Moon lists international investors from Singapore, China, America and Canada as those, “as sure as eggs is eggs”, who would raid our assets.

“There’s not a massive appetite within Cornwall to sell out to Chinese investors. But ultimately, this is an area that has been deprived for a very long time, there is an opportunity to create jobs to make sure that we get some economic stability within Cornwall. It would be a mistake, in my view, to not be taking advantage of that and letting international players dominate.”

“There is no western stage one processing capacity for tungsten from concentrate into the first stage of refined product,” says Mark Burnett, chief executive officer of Strategic Minerals.

“[I’d be lying if I said] we hadn’t been contacted by a corporate party that is related in some way to China – but it’s rather inescapable. But to be clear, from a board, a company and a management and team perspective, we don’t want to take that route. We want to develop a tungsten mine in the UK that’s the highest-grade tungsten mine in Europe, and largely in the world.”

History has shown that when foreign investors buy domestic critical minerals assets, local communities can suffer.

Swiss mining company Xstrata took full control of the Windimurra Vanadium plant in Western Australia, for example, only to shut the mine down just months later in 2004. Hundreds of people were left jobless.

“They were protecting the South African market, the South African mines, so they didn’t want a new entrant into the market,” says Gavin Mudd, director of the Critical Minerals Intelligence Centre at the British Geological Survey.

“There was an extension from the gas pipeline built for that, so it could actually have a gas fired power station and therefore, in theory, cheaper electricity. That was subsidised by something like $100m or $200m by the West Australian government. To have that facility mothballed was a huge waste of taxpayers’ money.”

For now, momentum is on the side of British miners. But while the UK may be seeing its own ‘gold rush’, the danger is that government funding “freezes up and dries up”, says Burnett.

As world powers race to secure their own critical minerals, Labour faces a choice: continue to invest in our own critical minerals and support our ‘Cornish boys’ or watch as others reap the rewards.

A government spokesperson said: “Securing our supply of critical minerals, including nickel, is vital for our industrial strategy, economic growth and clean energy transition.

“We’re working with UK industry and G7 partners to develop plans that will reinforce our supply chains for the long term, increase the resilience of our economy and drive forward our Plan for Change.”