The UK’s power sector can move forward with greater certainty after regulator Ofgem announced a £28bn investment programme into the UK’s transmission and distribution networks on 4 December.

The package, which covers the five years from April 2026, also included key details of the regulated profits that the nation’s electrical grid monopolies can generate over the same period, including National Grid (NG), SSE (SSE) and Scottish Power, a subsidiary of Spanish utilities giant Iberdrola (ES:IBE).

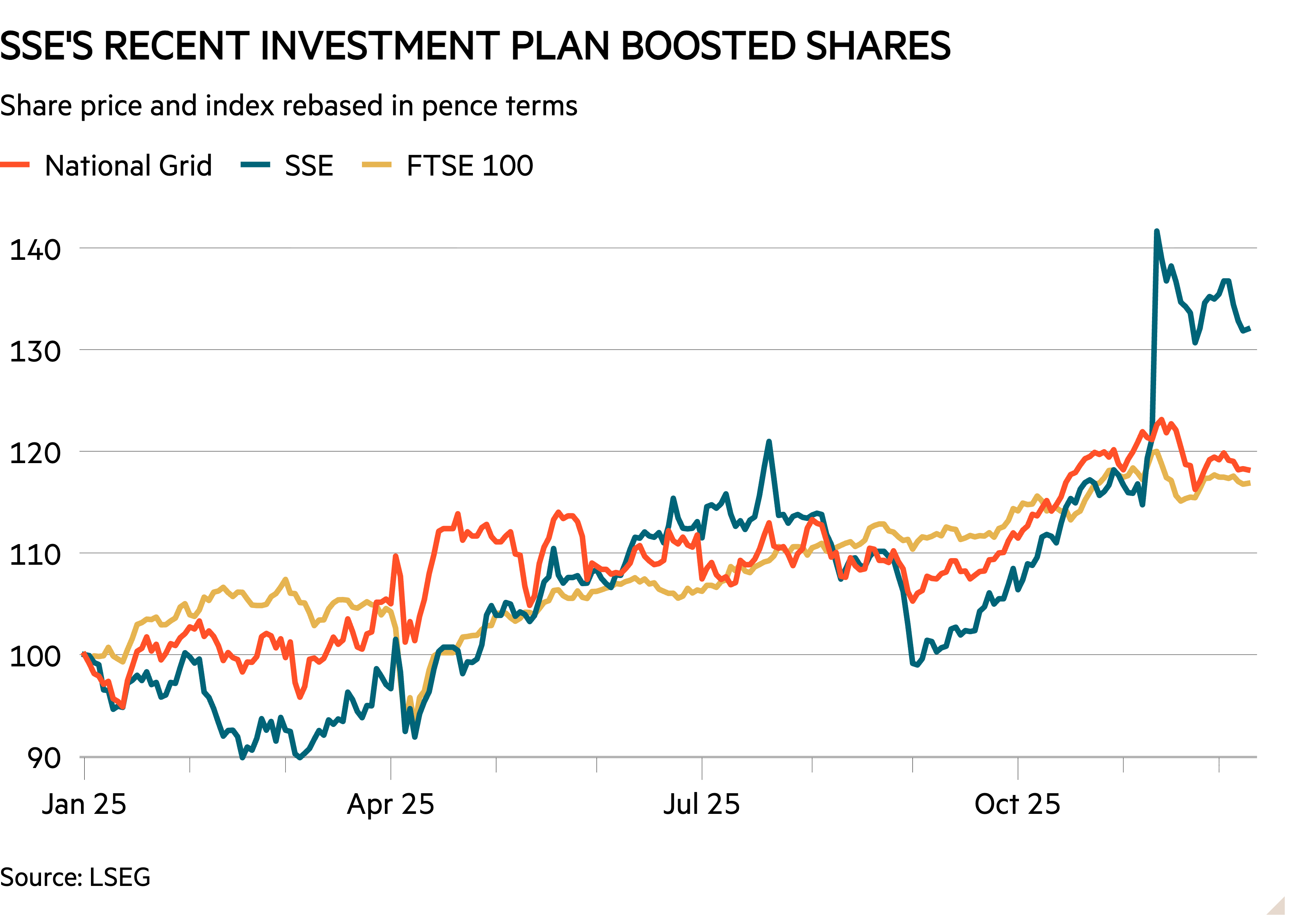

The companies themselves are largely positive about the regulator’s ‘final determination’, with SSE chief executive Martin Pibworth describing grid transmission as the “single biggest opportunity” for the company, when he upgraded its investment plan from £17.5bn to £33bn on 12 November.

But investors must now consider whether the risks and opportunities arising from the regulatory landscape are properly priced into the companies’ share prices, as well as the implications for their own utility bills.

The majority of the investment programme – £17.8bn – will be spent on the UK’s natural gas distribution and transmission networks, which are run by privately owned regional monopolies.

The remaining £10.3bn “will strengthen our electricity transmission network, improve reliability and expand capacity”, according to Ofgem. The networks had asked for £12bn in total allowed expenditure.

It is but one tranche of £90bn that Ofgem says will be invested into the UK’s power networks over the same period.

Necessary upgrades

The transmission network transports electricity at high voltage along the overhead lines we see attached to large pylons. It differs from the distribution network, which carries electricity along ‘last-mile’, lower-voltage lines into homes and businesses, and is subject to a separate, ongoing investment plan.

The grid needs to be upgraded. Demand is increasing as we electrify our everyday lives via electric vehicles and heat pumps, as well as from power-hungry data centres.

The existing grid is struggling to meet this efficiently. UK consumers often have to cough up for pricier electricity generated by local gas-fired power plants, while simultaneously paying wind farms to switch themselves off because the grid lacks sufficient capacity to transport the electricity they generate to the locations that need it.

This process, known as curtailment, has so far cost the taxpayer £1.4bn in 2025, according to website GB Renewables Map, up from £1.2bn in 2024.

Ofgem does not distribute the money itself, being but a regulator. The figure instead represents investment that National Grid and SSE can recoup from customers, which they do indirectly via the bills issued by suppliers such as British Gas, owned by Centrica (CNA), and Octopus Energy.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Impact on household bills

The net annual impact of the £90bn investment out to 2031 on average household bills will be about £30. The investment spend will cost around £108 per household, but will be offset by forecast efficiency savings of £80.

National Grid’s and SSE’s UK transmission businesses accounted for 26 per cent and 20 per cent, respectively, of their FY2025 group operating profit. Their distribution businesses are larger, with respective contributions of 32 per cent and 35 per cent.

The companies can recoup some of their investment in the first year, but the majority remains on their balance sheets, and is known as their regulatory asset value (RAV). They can then recoup this over a fixed period of time via household bills together with a regulated rate of interest, referred to as the return on equity.

Ofgem has set this rate at 5.7 per cent, assuming the investment is 55 per cent debt-financed. This is below the 6 per cent that the companies were requesting, but an improvement on the 4.55 per cent permitted in the previous investment cycle. That figure in the final determination resulted in a circumspect response from National Grid, which said it would review whether it was “both investable and workable”.

The programme also sets expenditure limits for the companies. These apply to the entire £90bn investment cycle, not just this initial tranche.

National Grid’s £30bn allocation was below the £35bn it had previously earmarked. A lower allocation means lower absolute profits, which may have disappointed some investors. SSE’s £32bn allocation was broadly in line with the company’s expectations.

Analysts at Barclays are positive on both companies, and argue that National Grid and SSE can increase earnings per share annually by 10 per cent and 8 per cent, respectively, over the medium term.

Against this backdrop, the companies’ valuations, on 13 times and 12 times analysts’ March 2027 earnings estimates, look undemanding.

Cashing in on transmission investment

The grid operators will naturally contract out their projects to the likes of Balfour Beatty (BBY), Costain (COST), Morgan Sindall (MGNS) and Renew Holdings (RNWH).

Balfour has described its power transmission business as “the number one and the most important” growth engine. Although it does not explicitly disclose transmission revenue, it has guided for it to quadruple between 2024 and 2028. It sits within the support services business, which accounted for 13 per cent of Balfour’s £5.15bn first-half revenues for FY2025.

Analysts at Panmure Liberum note that this business has high barriers to entry and that Balfour, as the UK’s largest provider of transmission cables, is well placed to benefit from elevated investment spend.