The market knows best, so the thinking goes. At any given time, it may overprice some companies and underprice others, but in the long run, the market will find the right price. Generally speaking, the businesses whose share prices are rising are doing well, and the ones whose share prices are falling are not.

And so it is with real estate investment trusts (Reits). A discount or premium to net asset value (NAV) is effectively a bet from the market on where a Reit’s NAV is heading. And the market tends to get those bets right.

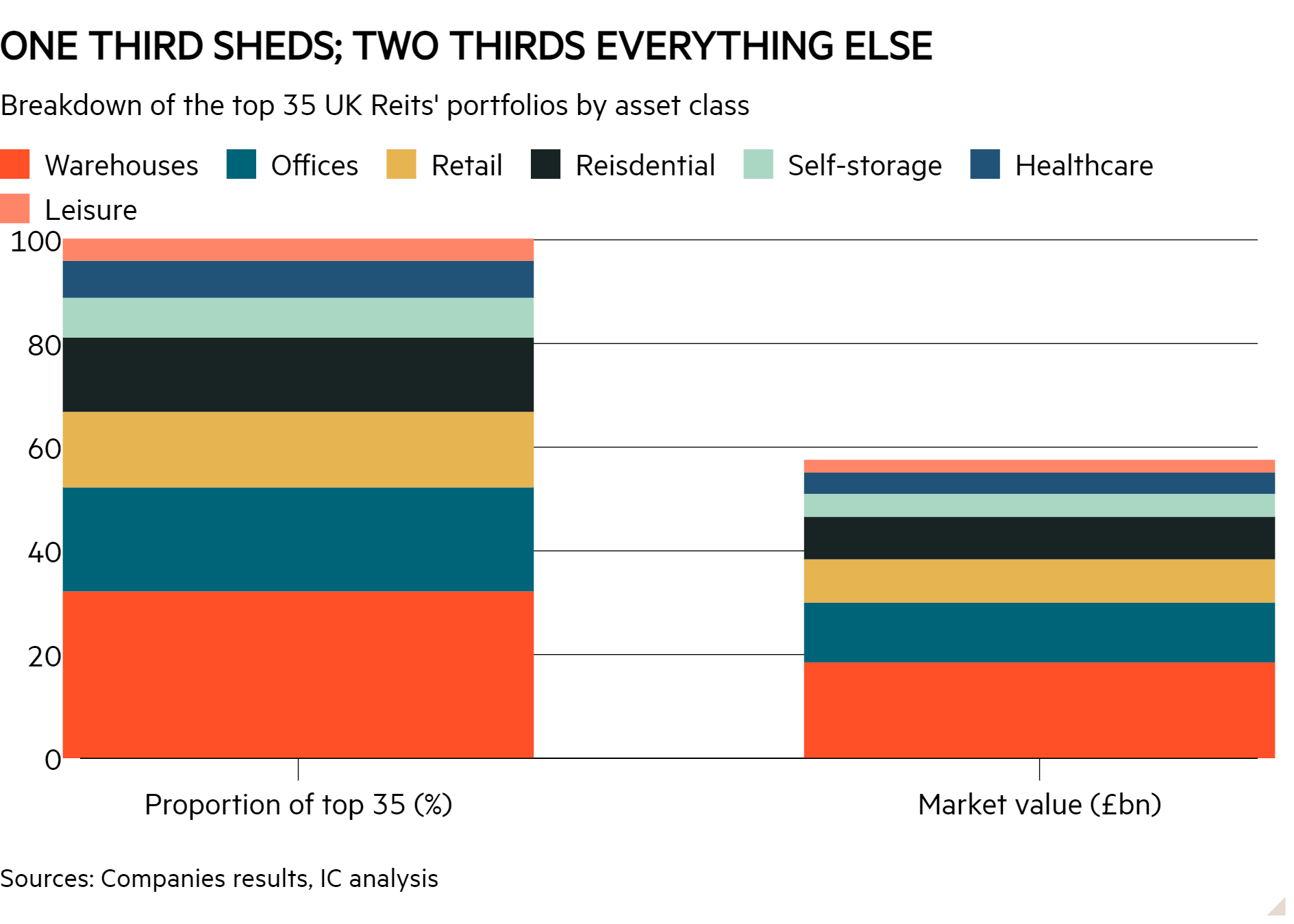

There are many issues with these simple assumptions, but it is worth looking collectively at the sector to examine where Reits are placing their money as it stands. What would such a portfolio look like? To find out, Investors’ Chronicle crunched the numbers on the sorts of buildings the top 35 Reits own, weighted according to their market capitalisation.

There are some caveats to the data, the first being the market capitalisation focus. This means our portfolio is weighted to the biggest companies, and that a Reit with a large portfolio of assets is prioritised even if those assets are out of favour, relatively speaking, with the market. There are two reasons for doing so: one, market cap is also partly a reflection of how well a given portfolio is performing, and in reality it is unlikely that returns on the largest portfolios would be so disappointing as to completely skew the sample. For example, Segro (SGRO), the largest Reit by market cap, has overtaken the likes of British Land by size in recent years precisely because its assets are deemed attractive. And the alternative to weighting by market cap would give undue focus to the smaller trusts that are struggling precisely as a result of their asset selections.

In only measuring Reits, the numbers of course also ignore properties owned privately, or by investment trusts such as HICL Infrastructure (HICL) and International Public Partnerships (INPP), or by non-Reit property companies such as Harworth (HWG) and Mountview Estates (MTVW). However, we have made three additional inclusions to our dataset: Grainger (GRI), which is becoming a Reit; Sirius Real Estate (SRE), which has Reit status for its UK operations but not its whole business; and Lok’n Store (LOK), which is not a Reit but operates like one.

The data also ignores potential future mergers which have yet to complete, including LondonMetric’s acquisition of LXi and Custodian’s acquisition of Abrdn Property Income. That said, if they were included these deals would not move the dial much on the final portfolio. A final caveat is that not all Reits are as forthcoming with their precise portfolio breakdown as others, given this is not an IFRS requirement. In those cases, we have estimated overall allocations based on the available data.

More sheds, fewer beds

To return to Segro: as things currently stand, the market does like the company, a lot. The Reit accounts for 18.6 per cent of the total value of the top 35 Reits, which explains why warehouses account for such a hefty chunk of the market’s overall portfolio. As previously observed, the company is worth more than its seven biggest rivals combined.

To understand what this does to the data, consider how European sheds rank fourth in our list of most popular asset classes. Even though two other shed Reits in the top 35 specialise purely in Europe, Tritax Eurobox (EBOX) and Abrdn European Logistics Income (ASLI), Segro alone owns 85 per cent of European warehouses in the top 35.

The data does more than reveal Segro’s dominance, though. It also shows the degree to which London offices remain a big part of the portfolio as it stands. Even accounting for the large discounts to NAV the market has placed on the major London-office-owning Reits, Landsec (LAND), British Land (BLND), Derwent (DLN) and Great Portland Estates (GPE), the asset class still accounts for 17 per cent of the top 35 Reits’ holdings.

Student accommodation is the next most popular asset class. As with Segro’s sheds, just one company owns the bulk of these: Unite (UTG). Its next largest rival scarcely comes close: Empiric (ESP) owns just 11.2 per cent of the student digs in the top 35 portfolio compared with Unite’s 88.8 per cent. In much the same way, Grainger owns most of the general residential assets in the portfolio.

Below that, the list becomes decidedly a mix of companies, and the preference for some asset classes over others is eyebrow-raising. UK self-storage assets ranked fifth due to the combination of Big Yellow (BYG), Safestore (SAFE) and Lok’n Store. General care properties, referring to hospitals, GP surgeries and primary care centres, ranked sixth thanks to the existence of Assura (AGR) and Primary Health Properties (PHP).

As for retail, there are a few ways to examine how it fares in the portfolio. On the one hand, the fact that shops, shopping centres, supermarkets and retail parks all rank below alternative asset classes like self-storage and healthcare speaks volumes about the move away from retail assets. Indeed, even though Shaftesbury Capital (SHC) is the sixth-largest Reit by market cap and the largest retail-owning Reit by market cap, most of its portfolio comprises non-retail assets – offices, leisure and residential.

On the other hand, the data also shows the diversity of retail assets. Warehouses are more or less the same beast as one another, differentiated mostly by size, quality and location. The same goes for offices. However, retail assets range from sprawling malls to off licences, from supermarkets to department stores. Even the category ‘shops’ contains everything from boutique West End clothes outlets to car dealerships.

If you bundle all these disparate UK retail assets together, they account for 12.5 per cent of the top 35’s holdings, cementing warehouses, offices and retail as the ‘core’ three asset classes. The reason for separating them is because the market also likes to do so. Shaftesbury Capital defines itself as different from Hammerson (HMSO) and NewRiver (NRR) because it argues that what it owns is worlds apart from what they own – and the other two would agree. Meanwhile, British Land is bullish on retail parks, but not so bullish on the supermarkets that Supermarket Income (SUPR) owns.

If we group all asset classes into broader categories, the result tells a different story about what sort of assets Reit investors like. Once again, warehouses come out on top, but by combining UK and European warehouses, their domination grows to 33 per cent of the market. Offices account for 20 per cent, general ‘retail’ accounts for 14.6 per cent, residential comes in at 14.3 per cent, while self-storage, healthcare and leisure come in between 4 and 8 per cent each.

The one company in the top 35 closest to this split is the perhaps aptly named Balanced Commercial Property Trust (BCPT), the biggest difference being its relative lack of exposure to residential. Still, there is clearly a gap between the speed at which a liquid secondary market, such as trading in Reit shares, can arrive at this kind of portfolio weighting, versus how long it can take for a Reit itself to buy and sell enough assets to arrive at this goal.

And just as discounts and premiums to NAV are assumptions about the direction of a Reit’s value, so too is this portfolio potentially an indication of the future path for Reits that define themselves as diversified. For BCPT to live up to its balanced moniker, this data would suggest it needs to buy more residential assets.

We can already see this happening elsewhere. British Land is selling offices to buy warehouses and build Canada Water, a large, mixed-use neighbourhood containing a lot of residential assets. The Reit’s portfolio balance is still far from the split of the top 35 portfolio, but with each warehouse it buys and each rental home it builds, it is getting closer to it. Likewise, LondonMetric’s acquisition of LXi exposes its portfolio to assets such as hotels and residential property for the first time, bringing it closer to the top 35 split.

Of course, to reiterate, the portfolio split is not an ideal example, merely a function of what is available on the public market. The exposure to rental social housing, for example, is the product of the existence of Triple Point (SOHO). Our belief has long been that the ideal exposure to this asset class is none because of the model’s myriad financial and ethical problems.

British Reits are (mostly) made in Britain

The final way of splitting up the portfolio is by location. The largest UK-listed Reits hold 86.7 per cent of their assets in the UK and the remainder in Europe. Uncovering the reason for this reveals much about the commercial real estate market. Generally speaking, it is hard to be blind to borders with real estate deals.

On top of everything else, such as the practicality and knowledge base required for dealmaking overseas, there are cultural factors to consider. Take warehouses, which make up just shy of 60 per cent of the European assets in the top 35. The world over, the role of sheds in online shopping drives tenant, investor and developer demand for the asset class. However, not all countries are internet shopping savvy. According to Ecommerce Europe’s 2023 report, 95 per cent of Britons shop online, a larger share than in any other European country. In Italy, where Segro owns 24 warehouses, just 57 per cent of people shop online, one of the lowest rates in Europe.

Meanwhile, just 83 per cent of French people shop online – or, put another way, 17 per cent of French people only shop offline – which has implications for Hammerson’s (HMSO) French retail holdings. We should also consider how the prevalence of working from home drives the office market.

An EU survey found just 14.5 per cent of Germany’s working population worked from home in 2022, the latest year for which the EU has data. By contrast, an Office for National Statistics (ONS) survey found that 25 to 40 per cent of the British working population worked from home in 2022 in any given week. This might explain why CLS Holdings’ (CLI) German office assets have outperformed its UK ones on occupancy, rental increases, and valuation over the last couple of years.

However you split the numbers, they remain subject to change. A decade ago, this table would have featured many more shopping centres and much less warehousing. The office market may be going through its own upheaval right now, but just as it is impossible to predict the future direction of markets, it is impossible to predict Reits’ own future plans. Our top 35 portfolio acts as a helpful guide, but investors may well spring a surprise or two in future.