Following what feels like an eternity of speculation, chancellor Rachel Reeves will reveal her cunning plan to fix the nation’s finances next Wednesday. Property will, as always, play a prominent role. Below, we run through some of the potential changes to tax and spending for the sector, and contemplate the potential winners and losers.

The homeowner

The government has seemingly decided against income tax hikes, but at the very least, threshold freezes that hit nearly all taxpayers are likely to be one notable feature of the Budget. That means the chancellor will want to portray other measures as progressive, in keeping with Labour’s roots.

Step forward, property. However real estate gets hit, it will almost certainly be the richest who will be hit the hardest. Doubling existing council tax rates for properties in the two highest bands, G and H, would be the bluntest and simplest way of raising revenue. This would result in average annual increases of £3,600 and £4,600 for each respective band, raising a cool £4bn in the process, according to think-tank Tax Policy Associates.

Band G properties, which have an average value of £750,000-£1.5mn, would generate 80 per cent of this total, and so are unlikely to escape the chancellor’s beady eye.

Holiday homeowners should also be on their guard. Since April, councils in England have had the power to double council tax on second homes. Around two-thirds have already done so. Such homes could, in theory, pay ‘double double’ council tax under these potential rule changes. Ouch.

There are several alternative, more nuanced approaches. One would be to adjust the charging structure of council tax, so that those in lower bands pay a smaller proportion of the total, and those in higher bands a larger one. Progressive, possibly, but also revenue neutral unless additional increases are layered on top.

Updating the valuations used to calculate council tax bands could be another change. Bands are still based on 1991 valuations, which Lucian Cook, head of residential research at Savills, describes as “arguably indefensible”. Such a move would be progressive, as the central London properties whose prices have subsequently skyrocketed would pay more, while those in less prosperous areas would pay less. The government could also design this so that it raised more revenue.

As is often the case with property tax reform, the biggest losers would be the likes of cash-poor, asset-rich great aunt Agatha, whose Islington four-bed has inconveniently quintupled in value since she bought it 30 years ago. In these cases, the government could defer increases until after the property is sold.

One would hope that automatic revaluations would be relatively simple in our data-rich age, but it gets tricky for properties with values above £1mn, according to Cook. This raises the unpalatable prospect of well-organised, well-funded groups of homeowners contesting their new valuations, cheered on by pockets of the press, and delaying revenue collection.

There is also our old friend, the ‘mansion tax’, an annual levy on the proportion of properties above a certain value. Labour last proposed such a tax at the 2015 general election, at 1 per cent on values in excess of £2mn, which they estimated would raise £1.2bn. The pledge was subsequently dropped after plenty of unfavourable press coverage but, a decade later, appears to be firmly back on the table.

Cook previously argued, in a 2015 paper for think-tank the Centre for Policy Studies, that the expense and complexity involved in administering such a tax would be disproportionate to the revenue raised – an opinion that he maintains.

The property tax reform most beloved of economists and think-tanks is to replace stamp duty, council tax and business rates in one fell swoop with a single annual land value tax on the unimproved value of land. The concept is beautiful in its simplicity but difficult to administer, and likely to be beyond the appetite of the current government.

“Ultimately, there’s no easy answer,” says Cook, before musing that “council tax reform might be the least bad option”. Moreover, any tax increase on premium properties will slow that part of the market, which in turn will trickle down to the rest of the housing market.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

The first-time buyer

First-time buyers are suffering from an affordability crisis, especially in London, where the average house price is nine times the average salary. Anything the government could do to ease these constraints would be welcome, not just to the buyers themselves, but to the wider property market, as well as the housebuilding, construction, building materials, builders’ merchants and home improvement sectors.

The easiest way for the government to do this would be through an equity loan scheme. The government could lend first-time buyers a percentage of a new-build property’s value, with an initial interest-free period, reducing their deposit requirements and initial mortgage costs.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it is. Under the Help to Buy scheme, which ran from 2013 to 2023, the previous government would lend first-time buyers up to 20 per cent of a new-build property’s value (up to 40 per cent in London). The loan was interest free for the first five years and enabled buyers to purchase a property with a significantly smaller deposit or mortgage.

Restricting the scheme to new-build properties should act to increase demand and incentivise the nation’s housebuilders to increase output.

The loans would also constitute capital expenditure, rather than day-to-day spending, and so would not be included in the all-important calculation of the 2029-30 current budget, which the chancellor, under her “ironclad” fiscal rules, has pledged to balance.

Despite its obvious appeal, such stimulus is unlikely to feature in the Budget. “No one really expects to see anything meaningful,” says Aynsley Lammin, building and construction analyst at Investec.

“I’m not sure that we will, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we saw an equity loan scheme,” says the slightly more optimistic Neal Hudson, founder and director at Residential Analysts.

Stamp duty relief is the other lever the chancellor could pull. First-time buyers already pay a lower rate of stamp duty land tax, enabling them to save as much as £5,000 relative to ordinary rates for properties worth up to £500,000. Further relief, or even a holiday, should in theory improve affordability, although an HMRC working paper in 2011 found that stamp duty relief for first-time buyers did not materially increase the number of buyers.

“There’s a growing sense that we might get a first-time buyer stamp duty cut or holiday,” says Anthony Codling, head of European housing and building materials research at RBC Capital Markets.

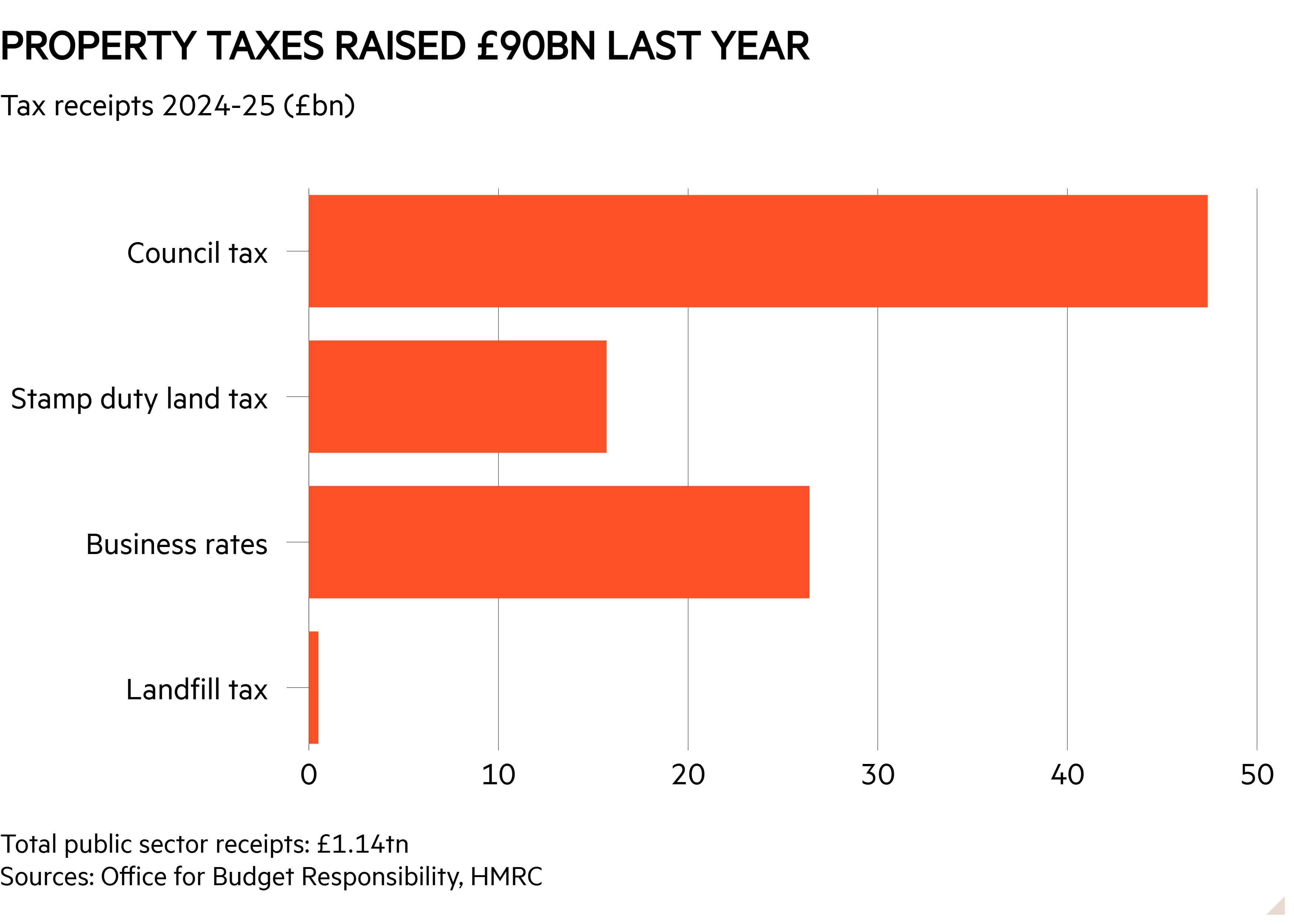

Stamp duty in general is a “deeply hated tax . . . that reduces labour mobility, results in inefficient use of land, and plausibly holds back economic growth,” according to Tax Policy Associates. Abolishing it, as the opposition has pledged, would be a good idea. Yet for all its economic benefits, it would also leave the chancellor with a further £14bn to find elsewhere. So it stays.

One final consideration for first-time buyers. Building societies have warned that halving the annual cash Isa tax-free allowance from £20,000 to £10,000 – another change under consideration – would deprive them of a source of cheap funding. They argue this will push up mortgage prices, particularly for the higher-risk products that target would-be homeowners, such as those requiring only a 5 per cent deposit.

The landlord

Britain’s army of small-time landlords have already been clobbered in recent years by stamp duty increases, rising mortgage costs and greater regulation, such as the additional risks and burdens that come with the recently passed Renters’ Rights Act.

There may be yet another blow in the offing, if, as has been mooted, the government levels national insurance on rental income. The Resolution Foundation think-tank has previously estimated that the reform could raise up to £3bn annually, but Hamptons reckons that a more realistic figure would be £1bn.

After all, over-65s account for a third of landlords, and those above state pension age don’t pay national insurance, while landlords could also skirt the tax by forming limited companies to own their properties, as many have already done.

Cook thinks such a reform is unlikely. “It’s difficult to administer and difficult to know what the impact will be,” he says.

The renter

There are unlikely to be any burdens or reliefs specifically for renters in the Budget, but tax increases for landlords tend to trickle down to their tenants, Renters’ Rights Act or no.

The housebuilder

Housebuilders have been vociferously encouraging of support for prospective homeowners, not least because the introduction of something like Help to Buy would materially boost industry profits. “We hope for targeted support for first-time buyers,” Bellway’s (BWY) chief financial officer, Shane Doherty, told Investors’ Chronicle in October.

“It is essential that government policy . . . supports homebuyers, especially first-time buyers,” said Barratt Redrow (BTRW) chief executive David Thomas on 5 November.

“The significant economic and social benefits of increased housing supply can only be unlocked by effective demand, particularly from affordability-constrained first-time buyers,” chimed in Taylor Wimpey (TW) chief executive Jennie Daly a week later.

While this is still unlikely to happen, housebuilders will want to see a Budget that calms the bond markets, in turn lowering their customers’ borrowing costs. Income tax rises could have helped here, given they may well have tempered inflation further and so hasten Bank of England rate cuts.

The sector would also like the government to hurry up in deploying the £39bn earmarked for affordable housing over the next decade. Bidding for grants doesn’t even start until February 2026, so the money is unlikely to stimulate much housebuilding in the near term.

What housebuilders definitely do not want is the abolition of the reduced rate of landfill tax, a tax on the disposal of waste at landfill sites. The (heavily) reduced rate is currently levied on materials such as soil and rubble. Abolishing it, as per proposals for the reduced rate to gradually taper away over the next five years, would mean an additional charge per tonne of £122, a thirty-fold increase.

This would add an average additional cost of £15,000 per new home, estimates industry body the Home Builders Federation (HBF), significantly reducing margins. “The government has got to reconsider its proposals . . . they will have a massive impact on viability everywhere,” says HBF executive director Steve Turner.

The commercial landlord

Commercial landlords will have a keen eye on any changes in business rates – the taxes paid by occupiers of commercial property, or by the landlords themselves if the property is vacant for more than three months. Labour had previously pledged “to replace the business rates system”. Instead, it is set to make the rules more complex.

Under the proposed changes, the occupiers of smaller retail, hospitality and leisure premises will continue to receive some form of relief, as was first implemented during the pandemic. Larger food retailers have been lobbying aggressively for inclusion in this, cautioning that to do otherwise risks driving food price inflation.

Those likely to be paying more under the changes are occupiers of properties whose values have increased between 2021 and 2024, most notably logistics premises and prime offices, reckons David Parker, national head of rating at Savills. He does not expect the changes to raise material additional revenue.