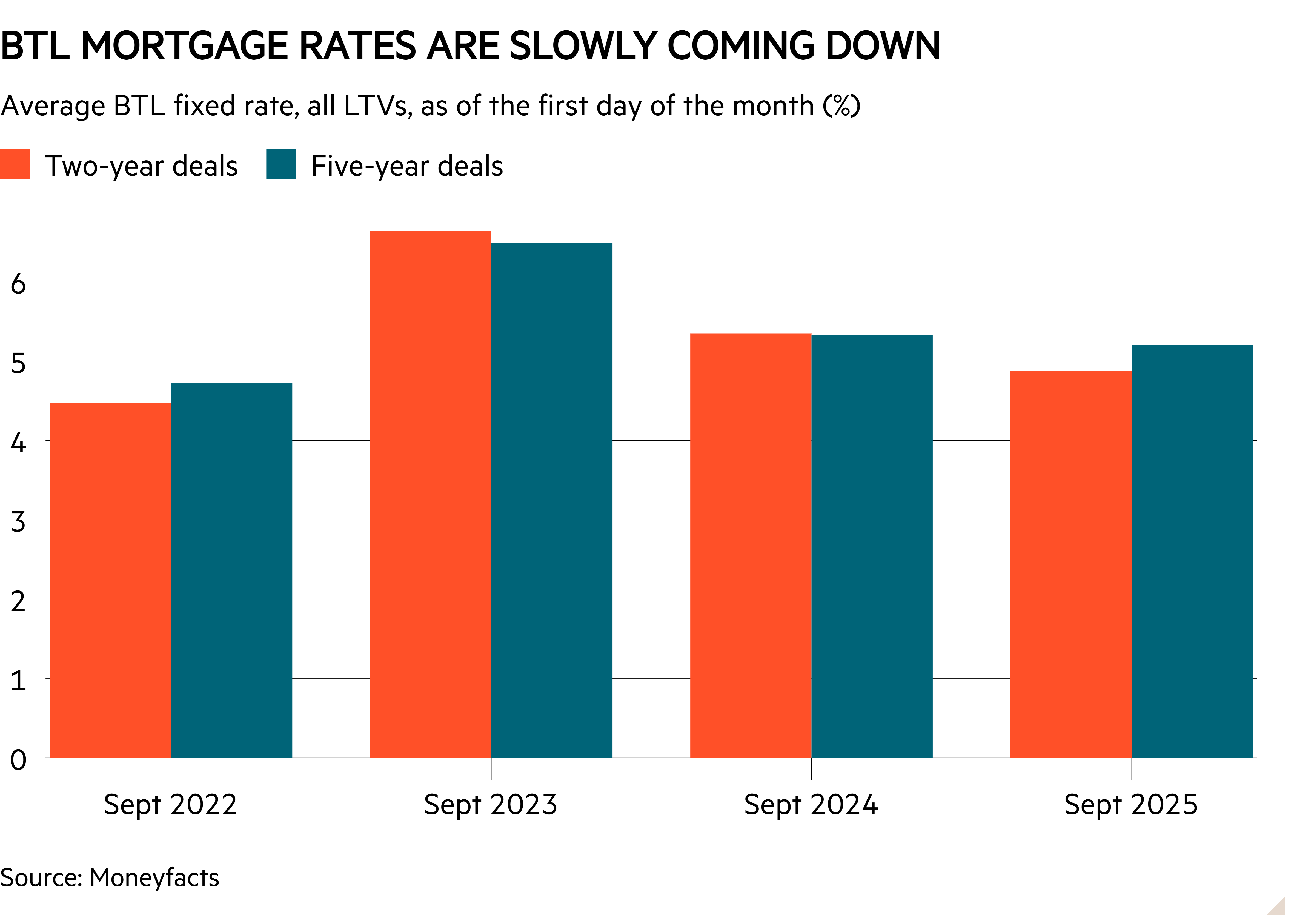

The good news first: buy-to-let mortgage rates are the lowest they have been in three years. That is, since Liz Truss’s ‘mini’ Budget sent gilt yields soaring, and pension funds and mortgage rates with them.

As at the beginning of September, average buy-to-let fixed rates stood at 4.88 per cent for two-year deals and 5.21 per cent for five-year deals, according to Moneyfacts. There were 4,597 products available on the market, the highest count since the firm started keeping records in November 2011.

More affordable mortgage rates have also allowed some landlords to improve the condition of their properties. Analysis of UK Finance figures by Paragon Bank showed that in the first half of 2025 there was a significant increase (54 per cent on the same period last year) in the amount taken out by landlords via buy-to-let remortgages for property improvements.

However, rates are nowhere near low enough to make up for all the other headwinds facing buy-to-let investing.

Firstly, some landlords are still to feel the rates shock. “Uncertainties over the path of interest rates, and the changes to mortgage interest tax relief embedded by April 2020, meant some landlords would have grabbed a five-year fixed deal for peace of mind,” explains Rachel Springall, finance expert at Moneyfactscompare.co.uk.

Those who did so about five years ago are soon in for an unpleasant shift. In September 2020, the average five-year fixed rate was 3.2 per cent, about 2 percentage points lower than today – on a £200,000 mortgage, that’s an increase in financing costs of around £4,000 a year.

Meanwhile, rental growth is flatlining. According to Hamptons, in August 2025, newly agreed rents in Great Britain actually fell by 0.4 per cent year on year; rental growth has now underperformed inflation for nine consecutive months.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

High financing costs erode landlord profits, particularly where property prices are high, to the point that the National Residential Landlords Association has urged its members to “look North” and will be holding its conference in Liverpool in November. “London remains the beating heart of the UK’s property sector, but opportunities are becoming fewer and farther between for landlords,” the organisation says.

London is the lowest-yielding region for buy-to-let investing – an average 5.7 per cent in 2024, according to Hamptons. As such, profits have tended to rely more on capital gains. Meanwhile, the average yield figure for the North East, the highest in the country, was 9.7 per cent.

On top of borrowing costs, the other persistent issue is policy uncertainty. Years in the making, the Renters’ Rights Bill is expected to become law before the end of the year. But as it involves major changes to the rental market, there will probably be a transition period. Details on this have been scant, so nobody knows when the changes will actually come into effect. Renters and landlords alike are aware that fixed-term tenancies will cease to exist soon, but not exactly when.

The autumn Budget might also bring further tax hikes for landlords. A number of changes to property taxes have been floated in the press, including the option of levying national insurance on rental profits.

Much would depend on how the measure is applied. Hamptons’ head of research Aneisha Beveridge notes that “the definition of ‘profit’ is key”. “If calculated before mortgage interest relief, it would amplify the chances of higher-rate taxpaying landlords having to pay tax on properties that are lossmaking,” she says.

This may well not materialise, but it doesn’t help confidence. It will take a lot more than lower mortgage rates to make buy-to-let investing attractive again.