But in his Labour Party Conference speech last year, Starmer said that there were “clearly ridiculous” areas included in green belt land, such as “disused carparks, dreary wasteland”.

These sites are a “grey belt” not a green belt, and their protected designation “cannot be justified as a reason to hold our future back”, he said.

So far, Labour has said grey belt land will be brownfield land in the green belt (which means sites that have been previously developed) and also green spaces “with little intrinsic beauty or character”.

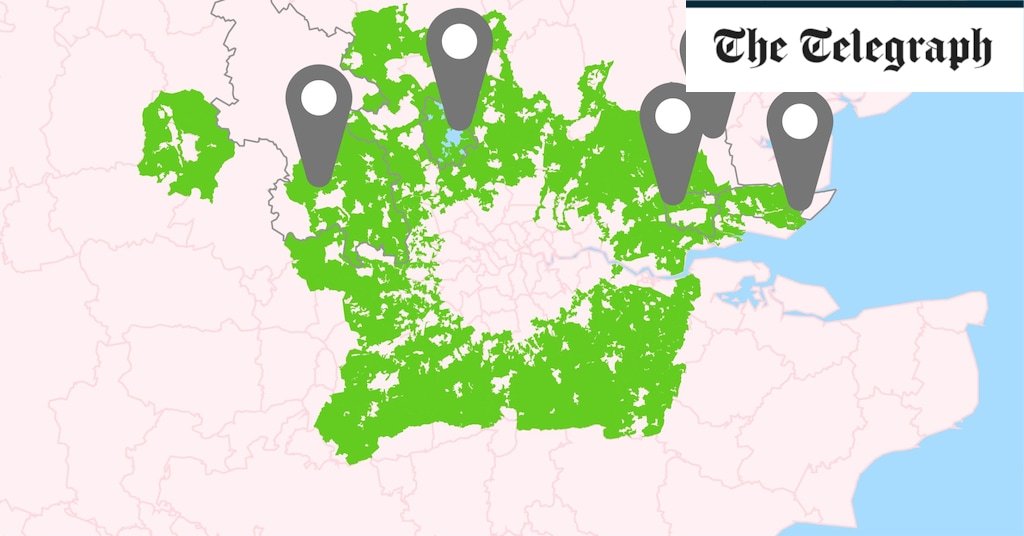

To identify potential grey belt land, LandTech looked at the sites that are listed on local authority brownfield registers and those that are derelict or vacant, using data from Ordnance Survey and Land Registry.

From this list, Quartermain removed the sites in flood zones or with particular environmental protections, such as designated ancient woodland and nature reserves.

He also discounted places that are particularly isolated, focusing only on ones next to an existing built-up area as these are the sites that will be targeted by developers. “It is not very useful to find a massive site in the middle of nowhere.”

On the remaining sites, LandTech assumed that only 60pc of space would be built on, to account for regulations around open areas and biodiversity net gain – new rules introduced in February that require developers in England to improve the natural habitat when they build.

“A lot of them are former industrial sites. A lot of them look like fields or paddocks or disused areas at the edges of settlements, but they are registered as vacant or derelict or they are on the brownfield register,” says Quartermain.

Three key game-changers

The formal definition should be imminent. Reeves said the Government is consulting on the new draft National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) “before the end of the month”.

This will be a game-changer for the green belt for three key reasons.

First, it will almost certainly reverse a change made to the NPPF in December 2023 under Michael Gove, the former housing secretary, which removed the requirement to undertake green belt review as part of their local plan process, says Simon Coop, senior director at planning consultancy Lichfields.

This means councils will be obliged to find sites within the green belt that they will allocate for development. Local authorities did this before, but the NPPF is also likely to widen the scope of what land should be considered appropriate for development.

The green belt chapter will likely include a detailed definition of what exactly will be considered to be grey belt land.

“How will it work in practice? I think in reality the overwhelming majority of grey belt land that actually comes forward will be on the edge of settlements,” says Coop.

Third, and this will be closely watched by housebuilders, the draft NPPF should outline how this land can be developed, says Coop.

The crucial question is whether local authorities will need to identify grey belt land and allocate it for development first, or if developers who think they have an appropriate site will be able to simply submit a planning application and outline themselves why the land should be considered as grey belt.